Illuminati

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the secret society. For the film, see Illuminata (film). For the Muslim esoteric school, see Illuminationism. For other uses, see Illuminati (disambiguation).

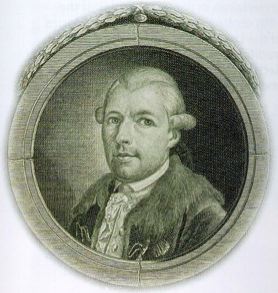

Adam Weishaupt (1748–1830), founder of the Bavarian Illuminati.

In subsequent use, "Illuminati" refers to various organizations claiming or purported to have unsubstantiated links to the original Bavarian Illuminati or similar secret societies, and often alleged to conspire to control world affairs by masterminding events and planting agents in government and corporations to establish a New World Order and gain further political power and influence. Central to some of the most widely known and elaborate conspiracy theories, the Illuminati have been depicted as lurking in the shadows and pulling the strings and levers of power in dozens of novels, movies, television shows, comics, video games, and music videos.

Contents

[hide]History

The Owl of Minerva perched on a book was an emblem used by the Bavarian Illuminati in their "Minerval" degree.

The goals of the organization included trying to eliminate superstition, prejudice, and the Roman Catholic Church's domination over government, philosophy, and science; trying to reduce oppressive state abuses of power, and trying to support the education and treatment of women as intellectual equals.[1] Originally Weishaupt had planned the order to be named the "Perfectibilists".[2] The group has also been called the Bavarian Illuminati and its ideology has been called "Illuminism". Many influential intellectuals and progressive politicians counted themselves as members, including Ferdinand of Brunswick and the diplomat Xavier von Zwack, the second-in-command of the order.[5] The order had branches in most European countries: it reportedly had around 2,000 members over the span of ten years.[1] It attracted literary men such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Johann Gottfried Herder and the reigning dukes of Gotha and Weimar.

In 1777, Karl Theodor became ruler of Bavaria. He was a proponent of Enlightened Despotism and his government banned all secret societies including the Illuminati. Internal rupture and panic over succession preceded its downfall.[1] A March 2, 1785 government edict "seems to have been deathblow to the Illuminati in Bavaria." Weishaupt had fled and documents and internal correspondences, seized in 1786 and 1787, were subsequently published by the government in 1787.[6] Von Zwack's home was searched to disclose much of the group's literature.[5]

Barruel and Robison

Between 1797 and 1798 Augustin Barruel's Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism and John Robison's Proofs of a Conspiracy both publicized the theory that the Illuminati had survived and represented an ongoing international conspiracy, including the claim that it was behind the French Revolution. Both books proved to be very popular, spurring reprints and paraphrases by others[7] (a prime example is Proofs of the Real Existence, and Dangerous Tendency, Of Illuminism by Reverend Seth Payson, published in 1802).[8] Some response was critical, such as Jean-Joseph Mounier's On the Influence Attributed to Philosophers, Free-Masons, and to the Illuminati on the Revolution of France.[9][10]Robison and Barruel's works made their way to the United States. Across New England, Reverend Jedidiah Morse and others sermonized against the Illuminati, their sermons were printed, and the matter followed in newspapers. The concern died down in the first decade of the 1800s, though had some revival during the Anti-Masonic movement of the 1820s and 30s.[2]

Modern Illuminati

Several recent and present-day fraternal organizations claim to be descended from the original Bavarian Illuminati and openly use the name "Illuminati." Some such groups use a variation on "The Illuminati Order" in the name of their organization,[11][12] while others such as the Ordo Templi Orientis use "Illuminati" as a level within their organization's hierarchy. However, there is no evidence that these present-day groups have amassed significant political power or influence, and they promote unsubstantiated links to the Bavarian Illuminati as a means of attracting membership instead of trying to remain secret.[1]Popular culture

Main article: Illuminati in popular culture

Modern conspiracy theory

Main article: New World Order (conspiracy theory)#Illuminati

There is no evidence that the original Bavarian Illuminati survived its suppression in 1785.[1] However, writers such as Mark Dice,[13] David Icke, Texe Marrs, Jüri Lina and Morgan Gricar have argued that the Bavarian Illuminati survived, possibly to this day. Many of these theories propose that world events are being controlled and manipulated by a secret society calling itself the Illuminati.[14][15] Conspiracy theorists have claimed that many notable people were or are members of the Illuminati. Presidents of the United States are a common target for such claims.[16][17]A key figure in the conspiracy theory movement, Myron Fagan, devoted his latter years to finding evidence that a variety of historical events from Waterloo, The French Revolution, President John F. Kennedy's assassination and an alleged communist plot to hasten the New World Order by infiltrating the Hollywood film industry, were all orchestrated by the Illuminati.[18][19]

Novels

The Illuminati (or fictitious modern groups called the Illuminati) play a central role in the plots of novels, such as The Illuminatus! Trilogy by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson; in Foucault's Pendulum by Umberto Eco; and Angels and Demons by Dan Brown. A mixture of historical fact, established conspiracy theory, or pure fiction, is used to portray them.References

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g McKeown, Trevor W. (16 February 2009). "A Bavarian Illuminati Primer". Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon A.F. & A.M. Archived from the original on 27 January 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Stauffer, Vernon (1918). New England and the Bavarian Illuminati. NY: Columbia University Press. pp. 133–134. OCLC 2342764. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- Jump up ^ Stauffer, p. 129.

- Jump up ^ Goeringer, Conrad (2008). "The Enlightenment, Freemasonry, and The Illuminati". American Atheists. Archived from the original on 27 January 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Introvigne, Massimo (2005). "Angels & Demons from the Book to the Movie FAQ - Do the Illuminati Really Exist?". Center for Studies on New Religions. Archived from the original on 27 January 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- Jump up ^ Roberts, J.M. (1974). The Mythology of Secret Societies. NY: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-0-684-12904-4.

- Jump up ^ Simpson, David (1993). Romanticism, Nationalism, and the Revolt Against Theory. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-75945-8.88.

- Jump up ^ Payson, Seth (1802). Proofs of the Real Existence, and Dangerous Tendency, Of Illuminism. Charlestown: Samuel Etheridge. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- Jump up ^ Tise, Larry (1998). The American Counterrevolution: A Retreat from Liberty, 1783-1800. Stackpole Books. pp. 351–353. ISBN 978-0811701006.

- Jump up ^ Jefferson, Thomas. "'There has been a book written lately by DuMousnier ...'" (in English). Letter to Nicolas Gouin Dufief. 17 November 1802. Retrieved on 26 October 2013.

- Jump up ^ "The Illuminati Order Homepage". Illuminati-order.com. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- Jump up ^ "Official website of The Illuminati Order". Illuminati-order.org. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- Jump up ^ Sykes, Leslie (17 May 2009). "Angels & Demons Causing Serious Controversy". KFSN-TV/ABC News. Archived from the original on 27 January 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- Jump up ^ Barkun, Michael (2003). A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. Comparative Studies in Religion and Society. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23805-3.

- Jump up ^ Penre, Wes (26 September 2009). "The Secret Order of the Illuminati (A Brief History of the Shadow Government)". Illuminati News. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Jump up ^ Howard, Robert (28 September 2001). "United States Presidents and The Illuminati / Masonic Power Structure". Hard Truth/Wake Up America. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Jump up ^ "The Barack Obama Illuminati Connection". The Best of Rush Limbaugh Featured Sites. 1 August 2009. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Jump up ^ Mark Dice, The Illuminati: Facts & Fiction, 2009. ISBN 0-9673466-5-7

- Jump up ^ Myron Fagan, The Council on Foreign Relations. Council On Foreign Relations By Myron Fagan

Other reading

- Engel, Leopold (1906). Geschichte des Illuminaten-ordens (in German). Berlin: Hugo Bermühler verlag. OCLC 560422365.

- Gordon, Alexander (1911). "Illuminati". In Hugh Chisholm. Encyclopædia Britannica 14 (11 ed.). NY: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- Le Forestier, René (1914). Les Illuminés de Bavière et la franc-maçonnerie allemande (in French). Paris: Librairie Hachette et Cie. OCLC 493941226.

- Markner, Reinhold; Neugebauer-Wölk, Monika; Schüttler, Hermann, eds. (2005). Die Korrespondenz des Illuminatenordens. Bd. 1, 1776–81 (in German). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. ISBN 3-484-10881-9.

- Melanson, Terry (2009). Perfectibilists: The 18th Century Bavarian Order of the Illuminati. Walterville, Oregon: Trine Day. OCLC 182733051.

- Mounier, Jean-Joseph (1801). On the Influence Attributed to Philosophers, Free-Masons, and to the Illuminati on the Revolution of France. Trans. J. Walker. London: W. and C. Spilsbury. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- Robison, John (1798). Proofs of a Conspiracy Against All the Religions and Governments of Europe, Carried on in the Secret Meetings of Free Masons, Illuminati, and Reading Societies (3 ed.). London: T. Cadell, Jr. and W. Davies. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- Utt, Walter C. (1979). "Illuminating the Illuminati". Liberty (Washington, D. C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association) 74 (3, May–June): 16–19, 26–28. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- Burns, James; Utt, Walter C. (1980). "Further Illumination: Burns Challenges Utt and Utt Responds". Liberty (Washington, D. C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association) 75 (2, March–April): 21–23. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- John Coleman (1997). Committee of 300.pdf. London: Global Insights Publications, 4th edition. pp. 15–18.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Illuminati. |

- Gruber, Hermann (1910). "Illuminati". The Catholic Encyclopedia 7. NY: Robert Appleton Company. pp. 661–663. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- Melanson, Terry (5 August 2005). "Illuminati Conspiracy Part One: A Precise Exegesis on the Available Evidence". Conspiracy Archive. Archived from the original on 28 January 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- Original writings of the Bavarian Illuminati compiled by Terry Melanson

| ||